This story was first published on May 13, 2021.

At school pickup, my son’s teacher squinted out onto the playground at me. “J-J-Jia-...” she said, then gave up. “Joseph’s mom. We can’t expect everyone to Americanize their names.”

The thing is, I did.

For 23 years, my name was Caroline. My immigrant parents chose “Caroline” for our new life in a small American town. It was the 1980s. Yu-Ying became Diana, Tai-Jen became Jane, Ruey-Der became Ray. As a preschooler, I didn’t know the words for what we did then, but what we were going for was assimilation, not ethnic identity.

Then when I got married, I changed my last name and my first name, reverting back to my Chinese birth name. We had just elected a president named Barack Obama (who’d gone by Barry as a child). If people could say “Barack,” they could handle “JiaYing,” right?

People change their names for all kinds of personal reasons. In 2002, 24 percent of name change petitioners replaced their name with something more generically American-sounding, according to Kirsten Fermaglich, author of “A Rosenberg by Any Other Name.” Only about 5 percent went the other direction and switched to a more ethnically identifiable name.

Saying no to anglicized names

Pamela Redmond, CEO of the baby names website Nameberry, still remembers what it was like when she was a kid in the ’50s and ’60s: If you weren’t named Barbara or Susan, basically you were a big weirdo. But now names are becoming more and more unusual, reflecting international cultures and traditions.

“The number of names in the American lexicon has just been increasing, increasing and increasing,” Redmond said. “America itself has become more diverse in terms of the kinds of names people use, the kinds of names that are acceptable. That is attractive.”

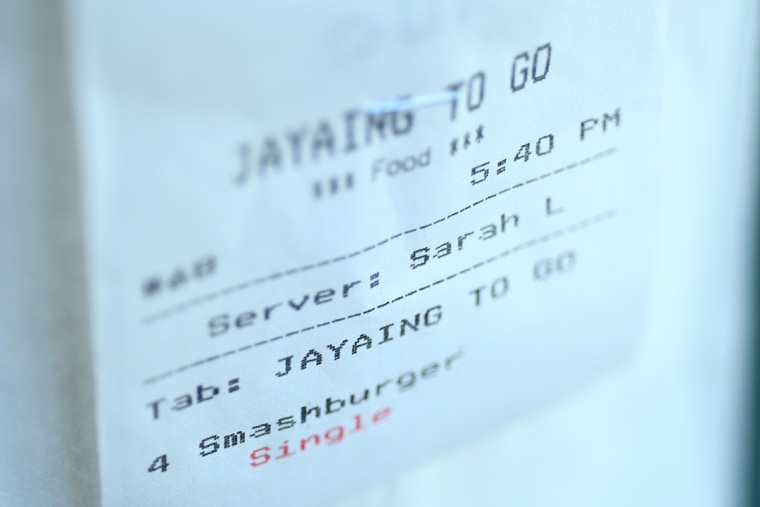

Having an uncommon name is a double-edged sword: you have to explain your name every time you meet someone new. I introduce myself with a mnemonic device, “JiaYing Grygiel, it rhymes with flying eagle.” At the same time, an uncommon name makes you the singular individual that a “Caroline” would never be.

“There is a really strong trend for people keeping their real names, not anglicizing their names or anglicizing the spellings,” Redmond said. “I think people are prouder of their names and less willing to give up that piece of their identity to fit in with some English-centric standard.”

The price of a weird name

True story: Did you hear the one about a Narayan, a JiaYing, a Thao and an Erika who went to a bar? The only person in the group with a job was Erika.

That’s right: An American-sounding name doesn’t just mean getting your Starbucks order spelled right. It means better job prospects.

A 2016 study by researchers at the University of Toronto and Stanford University showed that companies are more than twice as likely to call minority applicants with “whitened” resumes for interviews, even when they had the same qualifications. Masking your ethnic identity might mean changing your name, or omitting minority experiences, or — my favorite — adding hobbies like hiking and snowboarding.

I eventually did find a job, as a non-snowboarding JiaYing, after submitting approximately a million resumes. A dozen years and many attempts to spell “JiaYing Grygiel’’ over the phone later, the novelty of my name wore off. My own husband refers to me as “Sweetie,” because he is a kind man and also he is a teeny bit afraid of saying my name out loud.

I gave my own kids names that they’d always be able to find on those keychains in souvenir shops: Joseph and Paul. “Why didn’t you pick something like ‘Kai-shek’?” a friend asked.

Well, other than that Kai-shek was an authoritarian ruler, my husband wanted names that would look good on a CEO’s door. I wanted names that would be easy to pronounce in English or Mandarin. “Joe? Did I say that right?” said no one ever.

Friends from my “Caroline” past have painstakingly learned how to pronounce JiaYing. (It’s JAH-ing.) It’s a name you have to make an effort to learn how to say. But it’s 2021, we’re culturally enlightened, and we’re not going to change someone’s ethnically diverse name to something easy.

Except my mother. To this day, she still refers to me as Caroline.